Pressed Flowers in St Paul De Vence Pressed Flowers Art From St Paul De Vence

| Hospital at Saint-Rémy-de -Provence | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | 1889 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 58 cm × 45 cm (23 in × eighteen in) |

| Location | Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

Saint-Paul Asylum, Saint-Rémy is a collection of paintings that Vincent van Gogh made when he was a cocky-admitted patient at the Saint-Paul asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, since renamed the Clinique Van Gogh, from May 1889 until May 1890. During much of his stay at that place he was confined to the grounds of the asylum, and he made paintings of the garden, the enclosed wheat field that he could see outside his room and a few portraits of individuals at the asylum. During his stay at Saint-Paul asylum, Van Gogh experienced periods of illness when he could not paint. When he was able to resume, painting provided solace and meaning for him. Nature seemed particularly meaningful to him, trees, the landscape, even caterpillars every bit representative of the opportunity for transformation and budding flowers symbolizing the cycle of life. One of the more recognizable works of this period is The Irises. Works of the interior of the hospital convey the isolation and sadness that he felt. From the window of his cell he saw an enclosed wheat field, the subject area of many paintings made from his room. He was able to brand but a few portraits while at Saint-Paul.

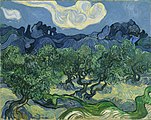

Within the grounds he also made paintings that were interpretations of some of his favorite paintings past artists that he admired. When he could exit the grounds of the aviary, he made other works, such equally Olive Trees (Van Gogh series) and landscapes of the local area.

Van Gogh's Starry Night over the Rhone and The Irises were exhibited at the Société des Artistes Indépendants on 3 September 1889, and in Jan 1890 six of his works were exhibited at the seventh exhibition of Les Xx in Brussels. Sadly, just as Van Gogh's work was gaining interest in the creative customs, he was not well enough to fully enjoy information technology.

Saint-Rémy-de-Provence [edit]

Van Gogh's room in Saint Paul de Mausole

Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, twelve miles northeast of Arles, lies but outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in southern France. Mentioned on several occasions by Nostradamus, who was born nearby and knew information technology a Franciscan convent,[i] it was originally an Augustinian priory dating from the 12th century, and has a particularly cute cloister.[2] A well-preserved fix of Roman ruins known as les Antiques, the most beautiful of which is le Mausolee, adjoins the property, and forms function of the ancient Graeco-Roman city of Glanum. Mont Gaussier, which overlooks the site, and the Alpilles range can exist seen in some of Van Gogh's paintings.[3]

Events leading up to stay at the Saint-Paul hospital [edit]

Following the incident with Paul Gauguin in Arles in December 1888, in which van Gogh cut off part of his left ear, he was hospitalized in Arles twice over a few months. Although some, such as Johanna van Gogh, Paul Signac and posthumous speculation by doctors Doiteau & Leroy, have said that van Gogh just removed part of his ear lobe and maybe a little more than,[four] art historian Rita Wildegans maintains that without exception, all of the witnesses from Arles said that he removed the entire left ear.[5] In January 1889, he returned to the Yellow House, where he was living, but spent the following month betwixt hospital and home suffering from hallucinations and delusions that he was existence poisoned. In March 1889, the police force closed his house after a petition past thirty townspeople, who called him "fou roux" (the redheaded madman). Paul Signac visited him in hospital and Van Gogh was immune home in his visitor. In Apr 1889, he moved into rooms endemic by Dr. Félix Rey, after floods damaged paintings in his ain home.[6] [7] Around this time, he wrote, "Sometimes moods of indescribable anguish, sometimes moments when the veil of fourth dimension and fatality of circumstances seemed to exist torn apart for an instant." Finally, in May 1889, he left Arles and traveled to the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.[eight]

In Saint-Paul Hospital [edit]

The Monastery of Saint-Paul de Mausole

View of the Asylum and Chapel at Saint Remy

1889

Formerly[nine] collection of Elizabeth Taylor (F803)

On 8 May 1889, van Gogh voluntarily entered the asylum[10] of St. Paul[xi] near Saint-Rémy in the Provence region of southern France.[12] Saint-Paul, which began as an Augustine monastery in the 12th century, was converted into an asylum in the 19th century.[3] It is located in an area of cornfields, vineyards and olive copse at the fourth dimension run by a one-time naval dr., Dr. Théophile Peyron. Theo arranged for 2 minor rooms—adjoining cells with barred windows. The second was to be used as a studio.[13]

Van Gogh was initially confined to the immediate asylum grounds and painted (without the bars) the world he saw from his room, such as ivy covered copse, lilacs, and irises of the garden.[10] [14] Through the open up bars Van Gogh could also see an enclosed wheat field, subject field of many paintings at Saint-Rémy.[15] As he ventured outside of the asylum walls, he painted the wheat fields, olive groves, and cypress copse of the surrounding countryside,[xiv] which he saw as "characteristic of Provence." Over the course of the year, he painted near 150 canvases.[10]

The imposed regimen of aviary life gave Van Gogh a hard-won stability: "I experience happier hither with my work than I could be exterior. By staying here a good long time, I shall have learned regular habits and in the long run the result will be more order in my life."[14] While his time at Saint-Rémy forced his management of his vices, such as coffee, booze, poor eating habits and periodic attempts to swallow turpentine and paint, his stay was not platonic. He needed to obtain permission to go out the asylum grounds. The food was poor; he more often than not ate only staff of life and soup. His only apparent grade of treatment were two-hr baths twice a week. During his year there, Van Gogh would accept periodic attacks, possibly due to a grade of epilepsy.[16] By early 1890 van Gogh'southward attacks of illness had worsened and he believed that his stay at the asylum was not helping to brand him better. This led to his plans to motility to Auvers-sur-Oise just north of Paris in May 1890.[17]

The corridor [edit]

The view downwardly the hallway of many arches is i of profound solitude. The use of contrasts creates greater tension. A lone person in the corridor appears lost, like to the way Van Gogh was feeling. In March 1889, Van Gogh wrote to his brother that a signed petition from his neighbors [in Arles] designated him as unfit to live freely, "shut up for long days under lock and cardinal and without warders in the isolation cell, without my culpability being proven or fifty-fifty provable."[18]

In a letter to Theo in May 1889 he explains the sounds that travel through the serenity-seeming halls, "There is someone hither who has been shouting and talking similar me all the time for a fortnight. He thinks he hears voices and words in the echoes of the corridors, probably considering the auditory nervus is diseased and over-sensitive, and in my case it was both sight and hearing at the same time, which is usual at the onset of epilepsy, according to what Dr. Félix Rey said one twenty-four hour period."[19]

Anteroom of Saint-Paul Infirmary [edit]

-

Corridor in Saint-Paul Hospital, Oil color and essence over black chalk on pinkish laid ("Ingres") newspaper

1889

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (F1529)[20] -

Entrance Hall of Saint-Paul Hospital, Black chalk, brush and thinned oil on pinkish newspaper,

1889

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F1530)

Corner of Saint-Paul Hospital [edit]

Van Gogh completed 2 versions of the corner of Saint-Remy hospital gardens. Van Gogh was descriptive in a letter of the alphabet to Émile Bernard of the setting for these paintings:

"A view of the garden of the asylum where I am, on the right a gray terrace, a section the house, some rosebushes that have lost their flowers; on the left, the earth of the garden – red ochre – globe burnt by the sunday, covered in fallen pine twigs. This edge of the garden is planted with large pines with carmine ochre trunks and branches, with light-green foliage saddened by a mixture of black. These tall trees stand out against an evening sky streaked with violet confronting a yellowish background. High up, the yellow turns to pink, turns to green. A wall – blood-red ocher once again – blocks the view, and in that location's nothing above information technology simply a violet and yellowish ochre hill. Now, the outset tree is an enormous trunk, but struck past lightning and sawn off. A side branch, thrusts upwardly very high, withal, and falls downward once more in an avalanche of dark green twigs. This dark giant – like a proud man brought low – contrasts, when seen every bit the graphic symbol of a living beingness, with the pale smile of the last rose on the bush, which is fading in front of him. Under the trees, empty rock benches, dark box. The sky is reflected yellow in a puddle after the pelting. A ray of lord's day – the last glimmer – exalts the night ocher to orangish – minor dark figures prowl here and there between the trunks."[21]

"You'll sympathise that this combination of red ochre, of green saddened with grey, of blackness lines that define the outlines, this gives rising a picayune to the feeling of anxiety from which some of my companions in misfortune often suffer, and which is called 'seeing red'."[21] [22] And what's more, the motif of the great tree struck by lightning, the sickly pink and light-green smile of the last flower of autumn, confirms this idea.[21]

-

The Garden of Saint-Paul Infirmary

October 1889

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

(F659) -

A Corner of Saint-Paul Hospital and the Garden with a Heavy, Sawed-Off Tree

1889

Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany (F660)

The garden [edit]

Fountain in the Garden of the Hospital Saint-Paul, Black chalk, reed pen and ink, May 1889, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F1531)

One twelvemonth before coming to Saint-Rémy Van Gogh wrote of a visit to an old garden, which shed light both on his interest in gardens and connection to their restorative effect: "If it had been bigger information technology would have made me think of Zola's Paradou, great reeds, vines, ivy, fig trees, olive trees, pomegranates with lusty flowers of the brightest orange, hundred-year-one-time cypresses, ash trees and willows, stone oaks, half-demolished flights of steps, ogive windows in ruins, blocks of white stone covered in lichen and scattered fragments of collapsed walls here and there among the greenery." Van Gogh gave reference to Émile Zola's La Faute de 50'Abbé Mouret, an 1875 novel about a monk who finds solace in an overgrown garden where he is nursed back to health by a young adult female.[23]

For the start calendar month of Van Gogh's stay he could not exit the grounds of the hospital, and then he looked to the garden where he painted flowers and trees. To his brother, Theo, he wrote, "When yous receive the canvases that I have done in the garden, yous volition see that I am not besides melancholy hither."[24]

In the commencement week in October Van Gogh made several paintings, such as The Mulberry Tree, The Reaper, and Entrance to a Quarry. He also made a painting of trees in the courtyard that he seemed proud of; he wrote, "I have ii views of the gardens and the asylum in which this place looks very attractive. I've tried to reconstruct information technology as it might have been, simplifying and accentuating the proud, unchanging nature of the pine trees and the clumps of cedar against the blue."[25]

-

Copse in the Garden of the Infirmary Saint-Paul

1889

Individual Collection (F642)

Van Gogh also made Flowering Rosebushes in the Asylum Garden too called Flowering Shrub that resides at Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F1527).

The Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital [edit]

-

The Garden of Saint-Paul Infirmary

October 1889

Private Drove (F640) -

The Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital

October 1889

Private Collection (F730) -

Trees in the Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital

October 1889

Private Collection (F731)

Pino Trees [edit]

Although Dec was a cold calendar month, van Gogh worked in the garden producing studies of pine trees in a storm and other work.[26]

Van Gogh may accept given Pine Trees with Figure in the Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital to Physician Joseph Peyron; his name is the starting time in the provenance for the work.[27]

Pine Trees and Dandelions includes "a pine trunk, pinkish and purple, and then the grass with some white flowers and dandelions, a piddling rose bush and some other tree trunks in the background right at the top of the canvass," Van Gogh wrote in a letter to his brother in May 1890.[28]

-

Pine Trees with Figure in the Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital

1889

Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France (F653) -

Path in Pino Copse with Effigy in the Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital

1889

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F733) -

Study of Pine Copse appears to exist within the walled Saint-Paul

1889

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F742) -

Pine Trees and Dandelions in the Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital

April–May 1890

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (676)

Trees and Undergrowth [edit]

Van Gogh explored the grounds of the asylum where he found an overgrown garden. He wrote, "since I take been here, I take had plenty work with the overgrown garden with its large pine trees, nether which there grows alpine and poorly-tended grass, mixed with all kinds of periwinkle." The paintings are of growth below ivy covered copse.[29]

Of the first of painting (F745), Van Gogh Museum comments, "The event of low-cal and shade created an almost abstruse pattern, with pocket-sized arcs of pigment covering the entire surface of the sheet."[29] The second (F746), likewise of undergrowth beneath trees, is made with small brushstrokes to create a blurred image that also shows the effect of light shining through the shaded trees.[xxx]

Ivy, originally Le Lierre is a painting Van Gogh fabricated May 1889.[31] Van Gogh incorporated the first version in his selection of works to exist displayed at Les 20, Brussels, in 1890.[32]

-

Ivy (Corner in the Garden of Saint-Paul Infirmary), 1889, 92 × 72 cm, Location unknown (F609)

Flowers [edit]

Equally the end of his stay in Saint-Rémy and the days ahead in Auvers-sur-Oise neared, van Gogh conveyed his optimism and enthusiasm by painting flowers. About the fourth dimension that Van Gogh painted this work, he wrote to his female parent, "But for ane's health, as yous say, information technology is very necessary to piece of work in the garden and see the flowers growing."[33] To his sis Wil he wrote, "The final days in Saint-Rémy I worked like a madman. Great bouquets of flowers, violet-colored irises, great bouquets of roses."[33]

Irises [edit]

Van Gogh made Irises from the irises in the asylum's garden. The painting seems influenced by Japanese ukiyo-eastward woodblock prints due to its close-upward views, large areas of bright color and irises appearing to overflow the borders of the frame. He considered this painting a study, which is probably why there are no known drawings for it, although Theo, Van Gogh'due south brother, thought improve of it and speedily submitted it to the almanac exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in September 1889. He wrote to Vincent of the exhibition: "[Information technology] strikes the eye from afar. The Irises are a beautiful report total of air and life."[34]

A single iris is the discipline of the second painting, smartly posed in the middle. Like rays of the sun, brush strokes radiate out from the plant. Iris, with ane full bloom, may have been painted before Irises that was filled with blooms.[35]

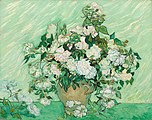

Roses [edit]

Lilacs [edit]

When Van Gogh worked on the Irises, he was besides working on Lilacs, both from the garden.[36] The Hermitage Museum, holder of this painting, describes it, "Van Gogh depicted a lilac bush in the hospital gardens, the broken, divide brushstrokes and vibrant forms recalling the lessons of Impressionism, yet with a spatial dynamism unknown to the Impressionists. This bush-league is full of powerful, bright free energy and dramatic expression. The modest natural motif is transformed past the master's temperament and the brilliance of his emotions. Embodied here in this fragment of an overgrown garden we find all of nature's life-giving forces. In rejecting Impressionism, Van Gogh created his ain artistic language, expressing the creative person's romantic, passionate and deeply dramatic perception of the globe."[37]

Floral still life [edit]

Van Gogh had non painted withal life during his stay at Saint-Rémy until the very last month of his year-long stay when he painted 4 striking bouquets of irises and roses.[38] To his sister Wil he wrote, "The concluding days in Saint-Rémy I worked similar a madman. Bang-up bouquets of flowers, violet-colored irises, great bouquets of roses."[33] Van Gogh's mother owned both upright versions of the irises and roses paintings held by the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art until her death in 1907.[38]

Vase with Irises [edit]

In one of the iris paintings he places the large bunch of violet irises confronting a harmonious pink background. Unfortunately, over time, the pink background has faded to about white. In the other, he use a contrasting yellow background.[38]

-

Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background

May 1890

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F678)

Vase with Roses [edit]

Van Gogh painted Still Life: Vase with Pink Roses shortly before his release from the Saint-Rémy asylum. As the terminate of his stay in Saint-Rémy and the days ahead in Auvers-sur-Oise neared, Van Gogh conveyed his optimism and enthusiasm by painting flowers. Almost the time that van Gogh painted this piece of work, he wrote to his mother, "Simply for one's wellness, as you say, it is very necessary to work in the garden and run across the flowers growing."[33]

The National Gallery of Art describes the painting, "The undulating ribbons of paint, practical in diagonal strokes, breathing the canvas and play-off the furled forms of flowers and leaves. Originally, the roses were pink—the color has faded—and would have created a contrast of complementary colors with the greenish." The exuberant bouquets of roses is said to be one of Van Gogh's largest, near beautiful nonetheless life paintings. Van Gogh fabricated some other painting of roses in Saint-Rémy, which is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art in New York Urban center.[39]

Butterflies [edit]

Van Gogh made at least two paintings of butterflies and one of a moth while at Saint-Rémy.

Poppies and Collywobbles [edit]

Debra Mancoff, writer of Van Gogh'due south Flowers, [40] described Poppies and Butterflies: "vivid carmine poppies and the pale yellow butterflies float on the surface of twisting nighttime stems and nodding buds, all against a xanthous-gold background. Although composed of natural motifs, van Gogh's layering of pattern in Collywobbles and Poppies suggests a decorative quality like that of a cloth or a screen." Mancoff compared this written report to the Japanese prints he admired.[41]

Long Grass with Collywobbles [edit]

London's National Gallery painting Long Grass with Collywobbles, besides chosen Meadow in the Garden of Saint-Paul Infirmary, [42] is a view of an abandoned garden with tall unkempt grass and weeds on the asylum grounds. The piece of work was made towards the end of his stay in Saint-Rémy.[43]

Green Peacock Moth [edit]

In May 1889 Van Gogh began work on Green Peacock Moth which he self-titled Expiry'due south Head Moth. The moth, called death'southward head, is a rarely seen nocturnal moth. He described the large moth'due south colors "of amazing distinction, black, grey, cloudy white tinged with crimson or vaguely shading off into olive green."[44] Behind the moth is a background of Lords-and-Ladies. The size of the moth and plants in the background pull the spectator into the work. The colors are vivid, consistent with Van Gogh'south passion and emotional intensity.[45] Van Gogh Museum'south title for this work is Emperor Moth. [46]

The Starry Night [edit]

The Starry Night depicts the view outside his sanitarium room window at night, although it was painted from memory during the day. Since 1941 it has been in the permanent drove of the Museum of Mod Fine art in New York Metropolis. Reproduced often, the painting is widely hailed as his magnum opus.[47]

The Wheat Field [edit]

Van Gogh worked on a group of paintings The Wheat Field based on the field of wheat enclosed by a wall that he could see from his cell at Saint-Paul Hospital. Beyond the field were the mountains from Arles. During his stay at the asylum he made virtually twelve paintings of the view of the enclosed wheat field and distant mountains.[48] In May Van Gogh wrote to Theo, "Through the iron-barred window I see a foursquare field of wheat in an enclosure, a perspective like Van Goyen, above which I come across the morning dominicus rising in all its glory."[49] The stone wall, like a motion-picture show frame, helped to brandish the changing colors of the wheat field.[l]

-

Dark-green Wheat Field, June 1889, owner unclear, possibly on loan to Kunsthaus Zurich, Zurich (F718 )

Mount Gaussier with the firm of Saint-Paul [edit]

Mont Gaussier, the ascendant hill of the Alpilles range, can exist seen from the streets of Saint-Remy.[51] Van Gogh by and large saw the Alpilles from his room or the grounds of Saint-Paul hospital. In Van Gogh'southward Le Mont Gaussier with the Mas de Saint-Paul the Alpilles are painted in yellow, green and purple.[52]

Left of Mont Gaussier is the Montagne des Deux Trous. In van Gogh'due south painting of this hill its dark holes are visible about the "undulating olive copse."[51]

-

Le Mont Gaussier with the Mas de Saint-Paul (b/w copy)

1889

Private collection (F725) -

Montagne des Deux Trous besides Olive Trees in a Mountainous Landscape (with the Alpilles in the Groundwork)

1889

Museum of Mod Fine art, New York, NY (F712)

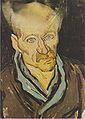

Portraits [edit]

Van Gogh, known for his landscapes, seemed to find painting portraits his greatest ambition.[53] To his sis he wrote, "I should similar to pigment portraits which appear after a century to people living then as apparitions. Past which I mean that I do not try to attain this through photographic resemblance, but my means of our impassioned emotions – that is to say using our knowledge and our modernistic sense of taste for color as a means of arriving at the expression and the intensification of the character."[53]

While Van Gogh had few opportunities to brand portraits, he completed at least three at Saint-Rémy.

François and Jeanne Trabuc [edit]

François Trabuc, who was the master orderly at Saint-Paul, and his married woman, Jeanne both sat for van Gogh. François Trabuc had a look of "wistful at-home" which van Gogh constitute interesting in spite of the misery he had witness at Saint-Paul and a Marseille hospital during outbreaks of cholera. He wrote to Theo of Trabuc's graphic symbol, a military presence and "small neat black optics". If it were non for his intelligence and kindness, his optics could seem like that of a bird of prey.[54]

Van Gogh describes Jeanne Trabuc as a "washed-out kind of a woman, and unhappy, resigned creature of fiddling consequence and so insignificant that I have a cracking desire to pigment this dusty bract of class. I've chatted with her a few times when I was doing some olive trees behind their little house, and she told me that she didn't think I was ill – indeed you would say the same right now if you could see me working."[55]

Portrait of a patient [edit]

While in Saint-Paul, Van Gogh wrote of other patients and their support for 1 another, "Though here there are some patients very seriously ill, the fright and horror of madness that I used to take has already lessened a neat deal. And though here you continually hear terrible cries and howls like beasts in a menagerie, in spite of that people get to know each other very well and help each other when their attacks come up on."[56]

Van Gogh wrote of a portrait he began in October 1889, "At the moment I am working on a portrait of 1 of the patients here. Information technology is odd that when y'all have spent some time with them and have got used to them, you lot no longer think of them as mad."[57]

-

Portrait of Trabuc; Chief Orderly at Saint-Paul Hospital

1889

Kunstmuseum Solothurn, Solothrun, Switzerland (F629) -

Portrait of Madame Trabuc (b/w copy)

1889

The Hermitage, Petrograd, Russia (F631) -

Portrait of a Patient in Saint-Paul Hospital

1889

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F703)

Interest in van Gogh'southward piece of work builds [edit]

While in Saint-Remy interest began to build in van Gogh's work:[58]

- Theo, Van Gogh's brother, wrote in July 1889, that Camille and Lucien Pissarro, Père Tanguy, Erik Theodor Werenskiold and Octave Maus, secretary of the Les 20 group in Brussels, had seen the paintings that he'd made in southern French republic. On Van Gogh'southward behalf, Theo accustomed an offer from Maus to exhibit Van Gogh'due south work at the Les XX group's upcoming exhibition.

- Van Gogh'south Starry Dark over the Rhone and The Irises were exhibited at the Société des Artistes Indépendants on the tertiary of September.

- In Jan 1890 6 of Van Gogh's works were exhibited at the 7th exhibition of Les XX in Brussels along with, amongst others, Paul Cézanne, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Signac and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Van Gogh's painting The Red Vineyard was sold to artist Anna Boch at the exhibition for 400 francs.

- In the same month an article is published "Les Isole: Vincent van Gogh" in the Mercure de France.

- Ten of Van Gogh'southward works were presented at the March 1890 Société des Artistes Indépendants. Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, and Pissarro were quite impressed with his works.

Over this fourth dimension, though, Van Gogh'southward health ebbed and flowed between periods of attacks, recovery, and resumption of painting.[58] In April 1890, most the terminate of van Gogh'southward stay at Saint-Paul's hospital, Theo wrote to his sister and mother, "I am then pleased that Vincent'south work is existence more than appreciated. If he were fit I believe that there would exist nil for me to desire, but information technology appears that this is not to be."[59]

The sale of Red Vineyard was the only sale of van Gogh's paintings fabricated during his lifetime.[60]

References [edit]

- ^ Lemesurier, P.: Nostradamus, Bibliomancer, New Page Books, New Jersey, 2010, p. x, ISBN 978-1-60163-132-9

- ^ Guide de Tourisme, Provence, Michelin, Clermont-Ferrand, 1990, p. 172, ISBN two-06-003-622-4

- ^ a b Lubin, A (1996) [1972]. Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh. New York: Da Capo Press. p. 186. ISBN0-306-80726-2.

- ^ Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent Van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. p. 106. ISBN0-8028-3856-1.

- ^ Wildegans, R. "Van Gogh's Ear". Dr. Rita Wildegans. Archived from the original on xix July 2011. Retrieved 27 Apr 2011"It can be said that with the exception of the sister-in-law Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, who had family-related reasons for playing down the injury, not a single witness speaks of a severed earlobe. On the opposite, the mutually independent statements past the principal witness Paul Gauguin, the prostitute who was given the ear, the gendarme who was on duty in the crimson-lite district, the investigating police officeholder and the local paper study, accord with the evidence that the creative person's unfortunate "self-mutilation" involves the entire (left) ear. The existing handwritten and clearly worded medical reports past iii different physicians, all of whom observed and treated Vincent van Gogh over an extended period of time in Arles as well as in Saint-Rémy ought to provide ultimate proof of the fact that the artist was missing an unabridged ear and not just an earlobe."

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Pickvance (1986). Chronology, 239–242

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 265–273

- ^ Hughes, Robert. Nothing If Not Disquisitional. London: The Harvill Press, 1990 p.145. ISBN 0-14-016524-X

- ^ "Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale". christies.com . Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ a b c "Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". Thematic Essay, Vincent van Gogh. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Olive Trees, 1889, van Gogh". Collection. Minneapolis Establish of Arts. Archived from the original on viii September 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Olive Trees, 1889, van Gogh". Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Callow, P (1990). Vincent van Gogh: A Life. Chicago: Ivan R Dee. p. 246. ISBNone-56663-134-three.

- ^ a b c "The Therapy of Painting". Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Van Gogh, 5 & Leeuw, R (1997) [1996]. van Crimpen, H. & Berends-Albert One thousand. (eds.). The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London and other locations: Penguin Books. p. F604.

- ^ Wallace (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853–1890). Alexandria, VA: Fourth dimension=Life Books. pp. 139–146.

- ^ Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola University Printing. p. 113. ISBN0-8294-0621-2.

- ^ Bordin, K; D'Ambrosio, L (2010). Medicine in Art. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust. p. 159. ISBN978-1-60606-044-5.

- ^ Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Saint-Rémy, 22 May 1889". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ Corridor in the Asylum, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ a b c "A Corner of the Asylum and the Garden with a Heavy, Sawed-Off Tree". Collection. Museum Folkwang. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ "The Garden of Saint Paul's Hospital, 1889". Permanent Drove. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ Helvey, J (2009). Irises: Vincent van Gogh in the garden. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 96. ISBN978-0-89236-226-4.

- ^ Hansen, Nichols, Sund, Knudsen, Bremen (2003). Van Gogh: Fields. Hatje Cantz Publishers for Toledo Museum of Art Exhibition. p. 13. ISBN3-7757-1131-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ van Gogh, 5; Suh, H (2006). Vincent van Gogh: A Self-portrait in Art and Messages. New York: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers. p. 270. ISBN1-57912-586-vii.

- ^ Hansen, Nichols, Sund, Knudsen, Bremen (2003). Van Gogh: Fields. Hatje Cantz Publishers for Toledo Museum of Art Exhibition. p. 15. ISBNthree-7757-1131-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) - ^ "Hôpital Saint-Paul à Saint-Rémy-de-Provence". Collections. Musée d'Orsay. 2006.

- ^ Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Saint-Rémy, 4 May 1890". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Undergrowth, 1889". Permanent Drove. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ "Undergrowth, 1889". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ "Corner in the Garden of Saint-Paul Infirmary". Van Gogh Gallery. 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "Theo van Gogh. Letter to Vincent van Gogh. Written 8 December 1889 in Saint-Rémy". WebExhibits.org. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d Mancoff, D (1999). Van Gogh: Fields and Flowers . San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 23, 28. ISBN0-8118-2569-8.

- ^ "Irises". Collection. J. Paul Getty Museum. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015.

- ^ Helvey, J (2009). Irises: Vincent van Gogh in the garden. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 46. ISBN978-0-89236-226-4.

- ^ Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh Saint-Rémy, c. 10–15 May 1889". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 25 Apr 2011.

- ^ "Lilac Bush". Search on Vincent van Gogh paintings. Land Hermitage Museum. 2003.

- ^ a b c "Irises". Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ "Roses". The Collection. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art. 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Mancoff, D (1999). Van Gogh's Flowers. London: Frances Lincoln Express. ISBN978-0-7112-2908-2.

- ^ Mancoff, D (2006–2011). "Vincent van Gogh Last Paintings". HowStuffWorks. Publications International, Ltd. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "Meadow in the Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital". Van Gogh Works. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved xviii April 2011.

- ^ "Long Grass with Collywobbles". Paintings. The National Gallery, London. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written 22 May 1889 in Saint-Rémy". Van Gogh Letters. van Gogh, J (trans.). WebExhibits (funded in role past U.Southward. Department of Education, Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Didactics). Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ Strieter, T (1999). Nineteenth-century European Fine art: A Topical Dictionary . Westport: Greenwood Printing. pp. 53–54. ISBN9780313298981.

- ^ "Emperor Moth, 1889". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "The Starry Night". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 Apr 2011.

- ^ "Rain". Collections. Philadelphia Museum of Fine art. 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola Printing. p. 104. ISBN0-8294-0621-2.

- ^ Fell, D (2001). Van Gogh'southward Gardens . United Kingdom: Simon & Schuster. p. 40. ISBN0-7432-0233-three.

- ^ a b Garrett, M (2006). Provence: a cultural history. Oxford and other locations: Oxford University Press. p. 73. ISBN0-19-530957-Ten.

- ^ Garrett, M (2006). Provence: a cultural history. Oxford and other locations: Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN0-nineteen-530957-X.

- ^ a b Cleveland Museum of Art (2007). Monet to Dalí: Impressionist and Modern Masterworks from the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art. p. 67. ISBN978-0-940717-89-three.

- ^ Garrett, M (2006). Provence: a cultural history. Oxford and other locations: Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN0-19-530957-X.

- ^ van Gogh, 5; Suh, H (2006). Vincent van Gogh: A Self-portrait in Art and Messages. New York: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers. p. 265. ISBNi-57912-586-vii.

- ^ Helvey, "Irises: Vincent van Gogh in the Garden," p. 108

- ^ van Gogh, Five; Suh, H (2006). Vincent van Gogh: A Self-portrait in Art and Letters. New York: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers. p. 271. ISBN1-57912-586-seven.

- ^ a b Hansen, Nichols, Sund, Knudsen, Bremen (2003). Van Gogh: Fields. Hatje Cantz Publishers for Toledo Museum of Fine art Exhibition. pp. 14–15. ISBN3-7757-1131-7.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) - ^ Bundrick, S (2009). Sunflowers. New York: Harper Collins. p. 308. ISBN978-0-06-176527-8.

- ^ van Gogh, V; Suh, H (2006). Vincent van Gogh: A Self-portrait in Art and Letters. New York: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers. p. 283. ISBN1-57912-586-vii.

External links [edit]

- Saint Paul de Mausole Monastery

- Saint Paul de Mausole Monastery (video)

Coordinates: 43°46′35″N 4°50′00″E / 43.7765°N 4.8334°E / 43.7765; 4.8334

0 Response to "Pressed Flowers in St Paul De Vence Pressed Flowers Art From St Paul De Vence"

Enregistrer un commentaire